Optic disc assessment

The cup to disc ratio barely scratches the surface. Approach the optic nerve assessment in the same way you might appreciate a work of art, or examine a “spot the differences” cartoon - the more you look, the more you see. Take your time and identify the important features.

Pearls

Some key features to consider when assessing optic discs:

Asymmetry

Size

Rim contour

Color and cup

Blood vessels and heme

Peripapillary atrophy (alpha and beta zone)

RNFL

Mnemonic challenge - think of something better than: A Smart Retired Collie Barks at Peripheral Rodents. Let’s delve a little more into each of these features.

Asymmetry

Less than 1% of non-glaucomatous nerves exhibit a difference in cup-to-disc ratio over 0.2 between nerves. If the right nerve has a C/D ratio of 0.7 and the left nerve has a C/D ratio of 0.5 without a clear etiology, think glaucoma until proven otherwise.

Size

Average disc diameter is around 1.9 mm vertically and 1.8 mm horizontally. Vertical diameter <1.5 mm is considered smaller than average, and >2.2 mm is considered larger than average.

Don’t be fooled by differences in disc diameter. Consider 1.2 million retinal ganglion cell axons exiting through scleral openings of 1.5 mm and 2.5 mm in diameter. A cup-to-disc ratio of 0.7 in a 2.5 mm nerve may not be pathologic, whereas a cup-to-disc ratio of 0.4 in a 1.5 mm nerve may actually be glaucomatous.

It’s easy to measure disc diameter at the slit lamp. Adjust the height of the slit beam to match the vertical disc diameter, then multiply the measured diameter in mm by the reciprocal of the lens magnification factor, or the “correction factor” (for 90D, x1.3; 78D, x1.1; 66D, x1.0; 60D, x0.9)

See below regarding the Disc Damage Likelihood Scale (DDLS) which includes disc size in the stratification of glaucoma risk.

Rim contour

Localized loss the the neuroretinal rim usually starts at the inferior and superior temporal poles of the optic nerve head, which is why nerves with glaucomatous damage exhibit “vertical elongation” of the central cup

The ISNT rule may help you catch early rim thinning at key locations - in normal eyes the thickness of the rim usually decreases in order from inferior, superior, nasal, to temporal. But as Captain Jack Sparrow would say, think of this rule as more of a guideline that will be disobeyed by some normal nerves once in a while.

Focal notching or complete loss of neuroretinal rim should signifies a disc at higher risk for further glaucomatous damage.

Color and cup

Glaucomatous nerves retain pink or orange color until very advanced stages of RNFL loss

Watch out for nerves with pallor out of proportion to degree of cupping - in appropriate cases, non-glaucomatous etiologies should be explored (anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION), compressional lesion to the optic nerve (tumor or hemorrhage), secondary optic atrophies due to papilledema, inflammatory and infectious causes)

The “laminar dot sign” can be seen in glaucomatous nerves as RNFL loss results in exposure of the lamina cribrosa within the scleral ring. However, this finding is present in a minority of normal eyes as well.

Blood vessels and heme

Look for NVD in patients at risk for PDR

Disc collaterals and tortuous veins can signify chronicity of IOP elevation

Bayonetting of vessels can be notable in deep cups as vessels “dive” out of side down the sheer cliff and re-emerge at the bottom of the cup, appearing to skip a segment

Baring of circumlinear vessels occurs when rim loss leaves vessels hanging like a rope suspended over a canyon; can also be a nonspecific finding

Nasalization of the central retinal artery and central retinal vein is seen with advanced cupping

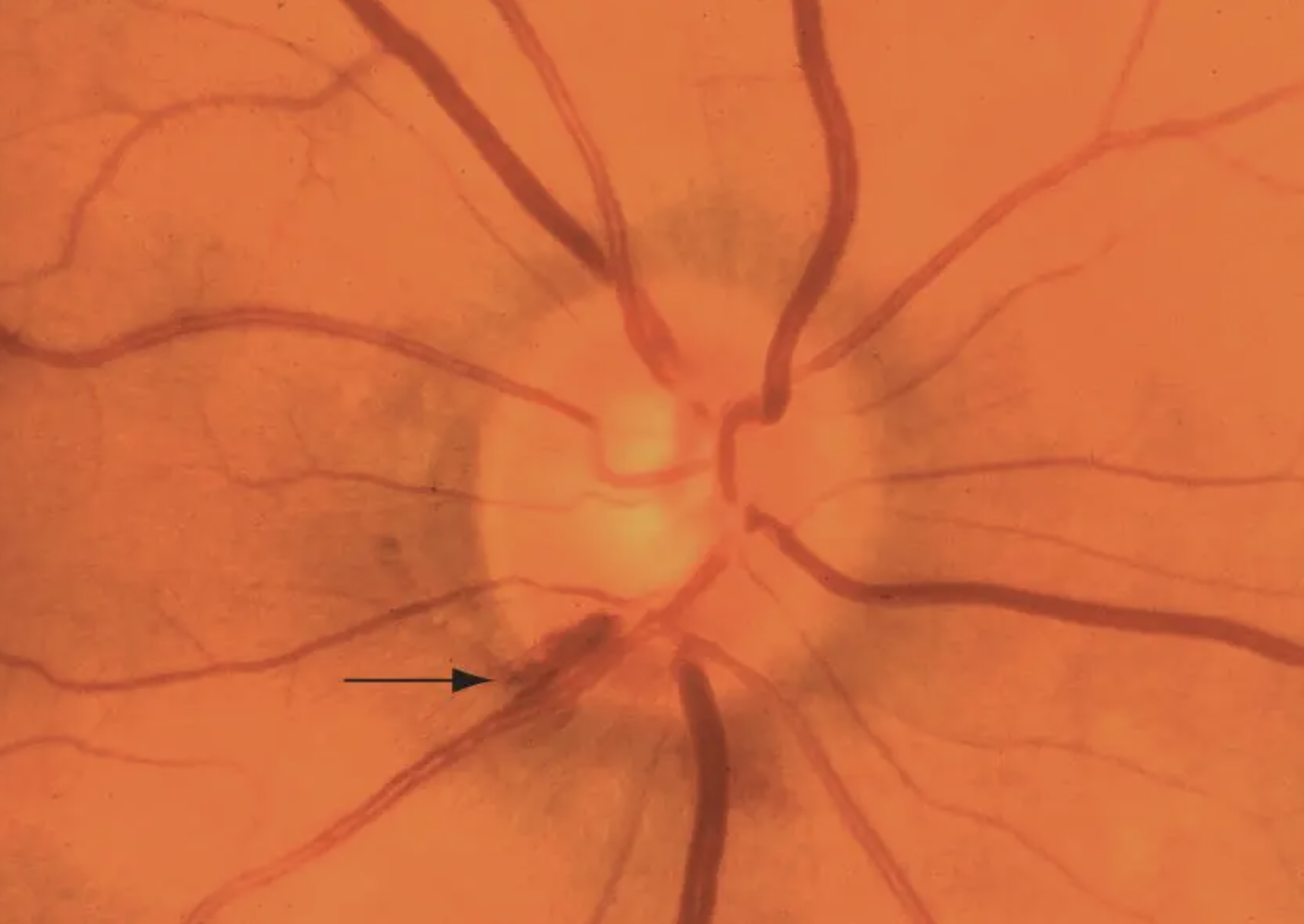

Nerve fiber layer hemorrhages (Drance hemorrhages, splinter hemorrhages) on the disc can be highly variable and difficult to spot, even on a dilated exam. Disc photos are much better at picking these up. They occur in about a third of glaucoma patients and remain for weeks to months, followed by localized notching and visual field loss. Disc hemorrhages are more common in normal tension glaucoma and less common in advanced glaucoma (perhaps due to extensive RNFL loss). Disc hemes need to be taken seriously because they signify higher risk for functional vision loss. Very rarely PVDs, diabetes, BRVOs, anemia and blood thinners can also be responsible for optic nerve head hemorrhages.

Peripapillary atrophy

PPA refers to the thinning and degeneration of the chorioretinal tissue just outside of the optic disc and the exposure of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), which gives the tissue a moth-eaten appearance.

PPA is not the same as pigment or scleral crescents which can be seen in tilted or myopic discs; these tend to be very uniformly dark or white in color, while PPA is patchy and irregular.

Zone α is a peripapillary crescent featuring RPE irregularities of hypo- and hyper-pigmented areas due to thinning of the chorioretinal tissue layer. Nasally, it is always separated from the disc by zone β or by the scleral ring if zone β is absent. Plenty of normal eyes have Zone α PPA so its presence doesn’t really mean anything.

Zone β is immediately adjacent to the disc and features total RPE and choriocapillaris atrophy, revealing the underlying sclera and large choroidal vessels. Zone β is rare in normal eyes and more common in glaucomatous eyes.

If all of that is too much to remember, you may be in luck - there are conflicting studies regarding the correlation between PPA and risk for glaucomatous progression.

RNFL

You can actually see axons of the RNFL if you look carefully at the posterior pole - it can help to use the red-free filter to highlight the axons and areas of focal loss. A healthy nerve fiber layer appears as bright striations; focal loss of nerve fibers appear as dark bands; diffuse loss just looks like a sad, dark desert - usually in the superior and inferior poles relative to the nasal and temporal areas.

Images © 2023 American Academy of Ophthalmology

DDLS (Disc Damage Likelihood Scale)

The vertical cup to disc ratio can be useful, but we must not forget its limitations. It is widely accepted as a way to describe the optic nerve head and gauge risk for glaucoma progression (e.g. it is used in the glaucoma risk calculator). However, we have all seen the 2.75 mm disc with C/D ratio of 0.75 and no vertical elongation that is followed with serial exams without any change.

The Disc Damage Likelihood Scale (DDLS), defined by Dr. George Spaeth in 2002, can be a useful supplement to the C/D ratio as a method for optic nerve head assessment. It takes into account 3 main categories of disc size (small, medium, large) and weighs more heavily the presence of focal rim thinning or notching.

Size of disc

Small (diameter <1.50 mm)

Average (diameter 1.50-2.00 mm)

Large (diameter >2.00 mm)

Ratio of the width of the rim (at the point where the disc rim is the most narrow) to the disc diameter in the same axis

In areas of total rim loss, circumferential extent of rim loss is given in degrees. Sloping (tilted discs) is not the same as absence of the rim

If you elect to stick with the C/D ratio, keep the DDLS scale in the back of your mind and jot down a few descriptors regarding vertical elongation, focal thinning, notching or rim loss.